Academic Privilege and the 2nd Generation Immigrant Experience

Council Estates, Grammar Schools & Oxbridge

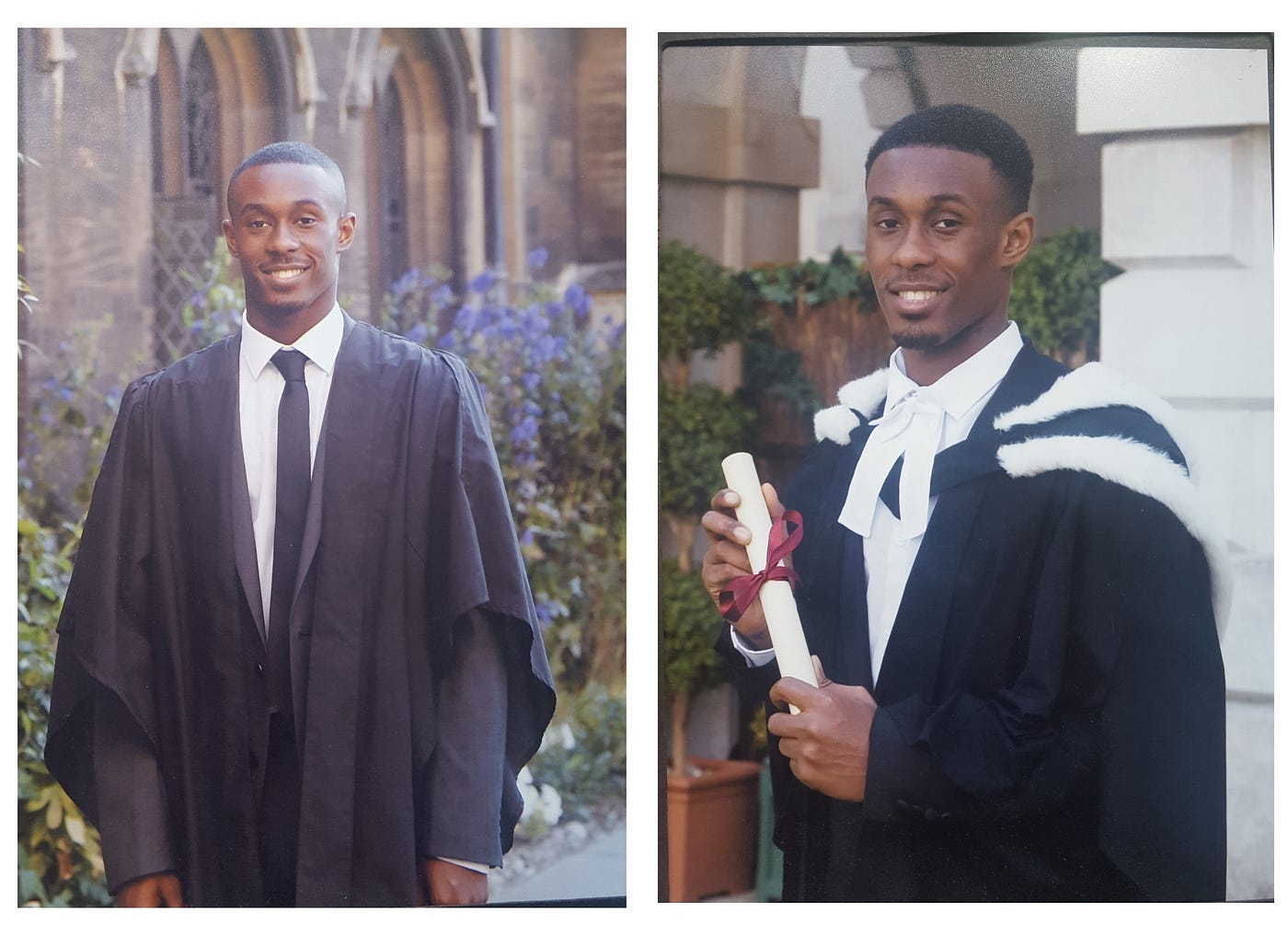

I originally wrote and published this (on Medium) in February 2018. This is the first piece of reflective writing that I publicly shared online. Exactly ten years post graduation feels as good a time as any to revisit.

As far as education is concerned, I have been extremely privileged. So privileged in fact that in a quiet, vulnerable moment of self-doubt it wouldn’t be hard to convince myself that such opportunities were quite frankly squandered on me.

The bullet-point version of the narrative reads much like most feel-good stories occasionally inserted in the mid-pages of local newspapers to illustrate that social mobility in the UK is alive and well and simply a matter of hard work and lofty ambition. Like most things the reality is in the detail. My parents came to the country in the early 1990s, during a flux that saw a number of young Africans from former British colonies migrate to the UK as students, economic migrants and political refugees. Like many others, we inhabited the inner-city areas and made homes in the crowded blocks of South London council estates, sharing rooms and beds with parent(s), siblings, and a regular rotation of extended family from “back home.”

We were the kids in primary school with home-done haircuts and hand me down wardrobes which featured the faux-pas sportswear of the era, (diadoras, new balances and Lecoq Sportif), many of which ironically today have reinvented themselves to become popular mainstream brands as opposed to the cheap alternatives to the untenable Nike and Adidas that we longed for. A few years down the line — when we were able to shop for ourselves — we frequented Wembley, Tooting, 9 Elms and East Street markets on Sunday mornings trying to purchase the knock off designer clothes that we aspired to own.

Our early tastes for exploration were satisfied by the independence provided by our parents’ relentless work schedules and the unaffordability of childcare. Older siblings, despite being children themselves, often played the role of surrogate parents when unaccompanied by adults. When you’re young and family holidays are reserved for American kids on TV shows, it is easy for your world perspective to be a 3-mile radius of your home. Even the country of origin which you proudly (or not so proudly) claimed is a distant memory or a fabrication based on the accounts of others.

As a kid, surrounded by other kids from vaguely similar backgrounds, the idea of being less-privileged, or at the very least “different” isn’t so pronounced. Sure, you may have been bullied for having shit trainers or having a funny sounding name, but for the most part you assume that everyone else lives more or less the same. At the age of 25, it’s hard to pin-point, but there are a couple of events that I think introduced the idea that where I grew up was a place that I should want to transcend. Nearly two decades on, the murder of 10 year old Damilola Taylor still produces images that are vividly etched in my memory: my mum hurriedly opening the door to our flat in Peckham, and her look of relief at seeing us all in one piece having arrived from primary school, the eerie silence in our living room, and the picture of his smiling face on the news in his bright red Oliver Goldsmith’s uniform, above an even brighter red ‘breaking news’ headline. At 7 years old, I was confronted with my own mortality in the only place I had ever known and the realization that home was not necessarily a safe place. However, it wasn’t until I was 11 years old, by now having received admission into a selective Grammar school in a leafy suburb of London/Surrey, over 10 miles south, was I more formerly introduced to how wealthier people lived.

Education has long been touted as society’s greatest equalizer. Though anecdotal, for my parents and countless others like them, this assertion was as good as the biblical truth. How frustrating then, I imagine, it must have felt when armed with undergraduate and master’s degrees from their respective countries, the jobs that many could obtain were as cleaners, kitchen porters and other roles that they were astoundingly overqualified for. This, all whilst suffering the hospitality that is often afforded to “foreigners” in their adopted homes. Nevertheless, the immediacy of the need to survive and cater to their young families makes necessity out of unfavorable circumstance. So where many of their own professional ambitions may have been indefinitely deferred, it was us, their children, who picked up the mantle — after all, despite being their offspring we were “British” kids in every other sense, born and raised within the system.

For whatever mixture of nature and nurture that was gifted me, this outlook served me just fine as I flourished academically. I was part of the gifted and talented programmes in primary school, through which for a few years I was even able to learn the violin for free. From my memory, these musical pursuits were not really encouraged by my parents, as with other creative or sports interests my siblings and I had. Of course, I cannot generalize and have friends whose parents strongly urged them to learn instruments, do taekwondo, attend drama classes or try out for local sports clubs, but if you find yourself nodding along relating to this anecdote, you would probably agree that my experience was not unique. Whether the financial cost or time required to accompany us on these endeavors was too much is a conversation many of us are yet to have, but what it clear is that for many of our parents, education is and was everything, which led to a great undervaluation of more expressive activities.

In 2005–2007, when the ‘happy slap’ craze was at its height and kids were being robbed for their Nokia 6310s on public transport, wearing an unfamiliar school uniform whilst travelling the breadth of South London twice a day was like having a red mark. My train passed through Mitcham Junction, Streatham, Tulse Hill, Herne Hill and Loughborough Junction on the way home, each stop requiring careful but discreet vigilance to avoid potential conflicts. The original ‘manz not hot’ experience for me was wearing a nike hoody or tracksuit top throughout every summer to hide the emblem on my school blazer whilst on my commute.

In effect, my day-to-day life in secondary school became a sharp juxtaposition. Old buildings, long corridors with photographs of headmasters, prefects and rugby captains stretching back into the early 20th century; and classrooms and playgrounds filled with predominantly (but not exclusively) white teenage boys were sights that I became accustomed to. Coming from a primary school where my classroom seats were occupied by black children, primarily Nigerian, you can imagine that this was somewhat of a culture shock. One only more pronounced by the fact that up until we moved away from the area a few short years later, every day I would return to the concrete labyrinth of the Aylesbury Estate, the exact antithesis of the green haven that my school was situated in.

Though I had many great times, there were countless instances where other students or members of staff made it overwhelmingly apparent to myself and friends from similar backgrounds that we were out of place. Ridiculous policies over haircuts, for instance, were something that disproportionately saw black boys receiving disciplinary actions. Having hair too short, by their definition below a Level 2 or too long (past the neck) were equally punishable. A good friend of mind with cornrows was constantly harassed by senior members of staff for the length and style of his hair until he eventually cut it off. Meanwhile, white students into the grunge and metal aesthetic, with their hair falling past their shoulders received no such treatment. As we grew into teenagers and our physicality approached maturity, my black and Asian friends were often labelled as trouble-makers and on one instance even rounded and accused of — no exaggeration — being “a gang” for the typical ‘naughty’ behavior that is often committed by students from all backgrounds, yet it was clear to us that they were not targeted in the same way.

Fast forward to my University years, and though this disproportionate policing of expression was not as prevalent, the sentiment of being the other was much the same. Though I’m still unpacking it all, the best way to describe my three years there was ‘uncomfortable.’ In an institution like Cambridge where my presence is so strikingly rare, it’s difficult not to become hyper aware of your ethnicity, financial situation, or accent. I have vivid memories of being turned away at colleges where I had seminars (which we called supervisions) by porter’s who refused to believe I was a student and having to argue my case whilst white counterparts strolled through without identification and asked multiple times if I was “visiting from home” when seeing friends at other colleges. Dealing with these micro-aggressions alongside trying to manage a challenging degree, maintain a “long distance” relationship, and have some semblance of a social life was a lot to handle. On some occasions, I would stay in my room for most of the day, too mentally and physically exhausted to leave for anything but to get food, and even then at times wanting to avoid going to the college hall or the communal kitchen to engage in small talk with my peers. The saying that comparison is the thief of joy could not have been more true, whilst everyone else seemed upbeat and well-adjusted, I was constantly tired and demotivated.

The fact that my grammar school experience failed to be the cultural bridge that would prepare me for the bubble that was Cambridge, I wonder how much more bizarre everything must have seemed for my peers who like the majority of the country attended their local comprehensive. You are immediately thrust into a strange world where people wear gowns to formal dinners in ancient, candle-lit college halls, reciting (in my view at the time) “weird latin shit” and signing your name into a book that was centuries old. Recalling the events of my first few days to friends on BBM sounded like a series of rituals performed before being initiated into the illuminati, and to the average person I effectively had been. I had joined this society of people supposedly destined for great things. To my family, I had achieved something amazing and they were proud. My dad in particular took every opportunity to tell his friends and work colleagues. I smiled and sheepishly accepted praise from all who felt compelled to congratulate me when I was in London but when I was back at University, there was a constant feeling of alienation that I couldn’t kick.

It is only recently that I have been able to verbalise some of my grievances and wasn’t surprised to hear that many of my peers could relate. Most of us had to confront our mental health at some stage and though I cannot apportion all blame to the University, for many of us that did not fit the typical Cambridge background, there is something undeniably toxic about the environment there that triggers such responses — depression, anxiety and even stress-induced psychotic episodes were not uncommon among some of the friends I made. With that said, when a group of us, four black and mixed raced men, sat down in a studio in East London, three or five years on from graduation to discuss our Cambridge experiences, when the question was posed whether or not in hindsight we would choose to attend Cambridge again, after a pause, there was a unanimous agreement that we would. Some months on from that encounter I question why that is the case.

With the general perception that an Oxbridge degree effectively means that you can walk into any job of your choice, it is perhaps patently obvious why you would attend. There is an air of respect and awe that comes with other’s acknowledgement of where you studied, an expectation that you must be somehow gifted or uniquely intelligent and thus your opinion tends to generally holds more weight. What’s more, in a climate where a University degree has over time become a signal of competence for oversubscribed entry-level employment, being an alum of an elite Russel Group or Oxbridge University represents a means of standing out from the crowd of eager graduates.

For the educationally privileged like myself, life in many ways can be viewed as a marathon of hoop jumping. Throughout much of our early lives our validation came from being successful academically, at the top of the food-chain in our respective ponds. Year on year from the age of 11 onwards we triumphantly ticked the checkboxes for society’s markers of success in regards to school attainment, GCSE and A-Level grades, followed finally by acceptance into a prestigious University, and it is possibly for this very reason that perhaps a genuine, robust sense of self-esteem divorced from our achievements can often fail to develop.

When this is significantly tested, you are forced to reevaluate your perception of self and what you truly value. It was clear to me that to some extent most of my decisions up until that point I had been from a place of fear. Keeping my options as broad as possible to defer the inevitability of choosing a path that perhaps I wasn’t really interested in because I had not made the effort to know who I was and what I enjoyed. I silently struggled throughout my degree, every year scraping by (in one literally by a few marks) until I ultimately left with a 2.2. Coincidentally or otherwise, it was during these years, my baptism in failure, that I started, possibly for the first time, really reflecting on what I did and did not want from life. Needless to say, the well-paid corporate job in the banking and finance industries which many of my Economics course-mates were losing sleep over attempting to secure, was not it. The prospect of competing, as I have done in the past, to be the only black guy in another overwhelmingly white, upper middleclass institution was daunting. I was burnt out and tired of jumping through hoops that I had no say in determining in the first place.

We all are burdened with pressure and expectations at various stages in our lives, especially within the context of existing in a capitalist society, but there is something particular about the pressure, often times self-imposed, that comes with being a child of immigrants. Although for the most part there isn’t the explicit expectation to financially provide for our parents as they approach their inevitable old age, for many of us, the desire to “pay them back” is a heavy motivating factor in our decisions. There isn’t a shortfall of rappers, typically from relatively deprived neighbourhoods both in the US and right here in the UK, that have expressed on songs their desire to “buy mum a house” — it’s the standard rags to riches narrative which is synonymous with the beautiful struggle that is becoming a “success”. For the financially modest but academically privileged, this sentiment is just as prevalent.

Working hard at school in order to get a ‘good’ job when you graduate is the formula for success that our parents and wider society has always sold to us. It is the end product of the sacrifices that they made and continue to make to exist and raise us in this country. In many ways it is beautiful, but I appreciate how it can also be damaging if it comes at the cost of stunting your personal growth and development as a well-rounded person.

One of the often underappreciated tragedies is that we are not often given the opportunity to explore and “find ourselves” like our wealthier counterparts can afford to do. Our twenties are the universally accepted time for exploration and risk-taking in rhetoric, but in in reality this is often discouraged. Sometimes this is for reasons overtly or seemingly out of your control. For instance, you may need to contribute to the household’s income on your return from University or care for a family member. I’m fortunate that this was not the case for me. Nonetheless, whilst the wealthy have the financial and social capital to cushion a few years of adventure abroad, pursuing a non-paying creative endeavor or starting up a new business, these sorts of activities are less accessible to us due to financial constraints, and even in instances when they are, can still be met with doubt, confusion or outright disdain from parents. These things are deemed to be unproductive, risky, or a waste of time, and in the case of the educationally privileged, a waste of years of academic effort. As such, it is through lack of opportunity or societal pressure that these valuable, enriching experiences are under-utilised, in favour of entry to the job market, sometimes in corporate careers that we have no genuine affinity to, almost immediately after 16+ years of formal education.

When I did not go down this route and was back home trying to figure it out, every conversation, even the genuine questions of my plans from parents and friends felt like I was being sized up, challenged to validate myself and my choices. The need to earn money, to have a set path ahead is stress-inducing as it is, but even more so when there are seemingly such high expectations placed on you. The great thing, four years on, is that although I do not have everything figured out, I am a lot more comfortable in the uncertainty. For the things that I do want to pursue, I am developing the discipline and patience to see them through and not be made stagnant by the perfectionism and paralysis by analysis that has often plagued me in the past. I have come to recognize that walking in faith is not exclusively a religious concept and is something we must all embrace in maneuvering in unfamiliar waters. Collaboration is one of the greatest hacks to progressing in most areas of our lives and finding your tribe is an endeavor that we must all make the effort to do. I have unlearned a lot of toxic behaviours and developed less socially conditioned views on relationships, spirituality, diet, family and the ever-elusive definition of success.

Most recently, I have learned that in a world where we often feel the need to conform to expectations or live up to some arbitrary standard to validate our self-worth, embracing who you are and freely expressing this truth is the most powerful thing that anyone can do.

As an immigrant, I could relate to most of the things you have experienced. I have sometimes struggled with "why did we even migrate?" to "what else would my parents have done given the situation?"

The unlearning of what we were taught at home and the beliefs we have formed has been an integral part of my adulthood. I am glad we have critical thinking to discern what is truth from what is a belief based on a few experiences. Therein lies our power.

Thank you for reposting this, Kwaku. These experiences you had rang true for me on so many levels. As reflective as I know I should be about the traumas of my family's past, I'm far from putting it so honestly, rawly and explicitly on paper. Thank you that I could experience this through you.